Anambra’s Ballot Bazaar: Nigeria’s Political Economy of Vote-Buying

Editor's note: In this piece, Lekan Olayiwola, a conflict analyst, takes readers into the 2025 Anambra elections’ vote-buying “market.” The researcher shows how poverty, political strategy, and institutional contradictions fuel a cycle that challenges trust and fairness.

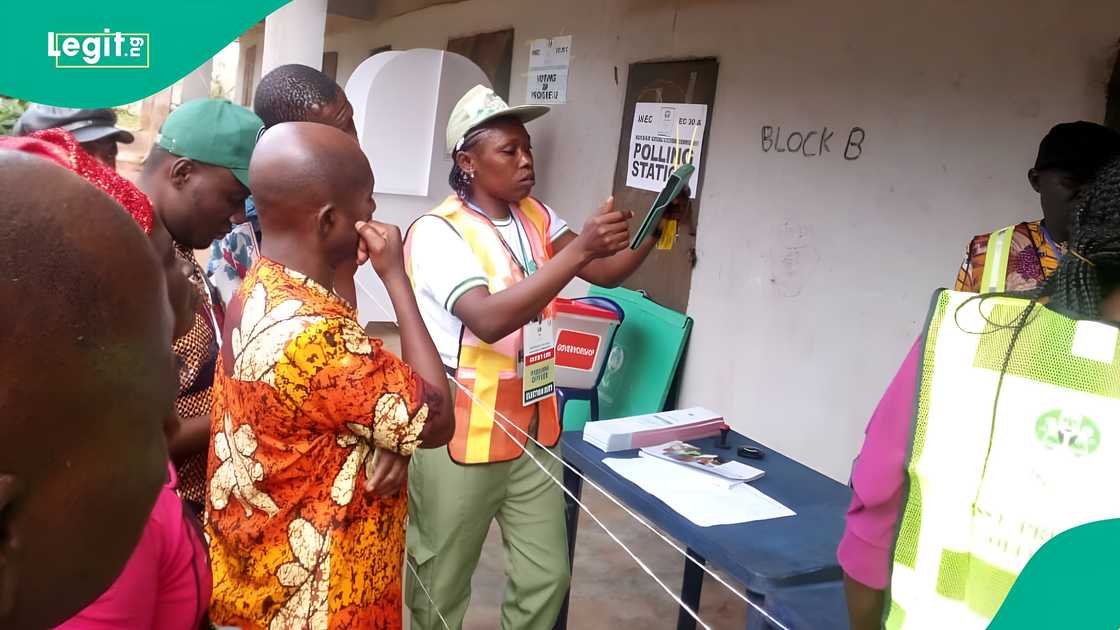

The media spotlight on the recently concluded Anambra elections exposed how money changed hands with the disquieting inevitability of market trade. Reported offers ranged from ₦3,000 to ₦30,000, reflecting a wholesale convergence of survival imperatives and political calculation which outstripped previous elections.

In 2013 and 2017, vote-buying was reported in concentrated pockets, though largely in smaller denominations and dispersed transactions; by 2021, inducements had become more strategic, targeting key urban wards, foreshadowing the high-density, high-value pattern witnessed in 2025.

Source: Twitter

Candidates decried ballot commodification, INEC dismissed the claims as unverified, yet the EFCC simultaneously announced arrests of suspected vote-buyers, laying bare a striking dissonance between institutional denial and enforcement. INEC and tens of thousands of security personnel orchestrated an orderly process, but could not secure trust, fairness, or dignity.

Anambra’s vote-buying mirrors a systemic inequality, institutional ambivalence, and the rational calculations of citizens navigating economic precarity. The ballots were protected, but the ethical grounding of democracy remained fragile.

Survival, strategy, and the market for votes

Beyond moralistic framing, a political economy underpins Nigeria’s “market” for votes. In regions like Anambra, where unemployment, inadequate social safety nets, and chronic service delivery gaps shape daily life, small sums of cash can function as emergency relief rather than mere inducement. A voter offered ₦5,000 to cast a ballot is not merely bribed; she is performing a transaction between survival and civic participation.

For political actors, this dynamic creates high stakes. In Anambra’s low-turnout context (below 22% of registered voters), mobilising even a few thousand votes can determine outcomes. Parties facing weak internal structures or highly competitive contests have strong incentives to deploy brokers, youth networks, and logistical machinery to secure those pivotal votes.

Institutions, contradictions, and trust

The Anambra episode exposed how institutional ambivalence shapes electoral realities. INEC focused its narrative on procedural success, PVC distribution, IReV uploads, and security deployment, while publicly denying incidents of vote-buying. The EFCC simultaneously executed arrests of low-level vote brokers. This simultaneous denial and enforcement confuses both the public and participants.

Read also

NUPRC Boss Gbenga Komolafe honoured at UK House of Lords for driving Nigeria’s energy reforms

In 2013, enforcement was patchy, in 2017, improvements in monitoring were uneven, and 2021 saw more arrests but limited narrative coherence. In 2025, these contradictions are more visible due to social media amplification and heightened national scrutiny.

Institutional credibility is about a coherent narrative and visible accountability. When one agency publicly negates the phenomenon while another acts upon it, cynicism grows. Citizens may question whether laws apply equally, whether institutions are capable, or whether elite impunity is tacitly tolerated. In effect, technical proficiency cannot substitute for relational legitimacy.

Viral social media imagery of bags stuffed with cash, videos of transactions proved to be a mix of legitimate reporting and misattribution. Fact-checkers like Dubawa identified several widely shared items as unrelated or misleading, complicating real-time responses. Yet authentic instances did exist and were corroborated locally, underscoring the need for robust, verifiable evidence collection mechanisms. Without these, even well-intentioned enforcement risks appear arbitrary or politically selective.

How Anambra 2025 differed

Vote-buying in Anambra’s 2025 election differed from traditional patterns observed in Nigeria in several notable ways. The density of transactions was concentrated; multiple high-value inducements were reported per polling unit, rather than scattered small-scale exchanges typical of 2013 and 2017. This pattern suggests strategic targeting of influential neighbourhoods or demographics capable of swinging tight contests.

The juxtaposition of INEC’s dismissal and EFCC’s arrests created a rare public spotlight on the coordination gap between monitoring and enforcement agencies. Whereas vote-buying has long been an open secret in prior elections, the Anambra case made the friction between procedure, enforcement, and narrative publicly legible.

Real-time uploads and observer networks allowed for monitoring beyond traditional polling units, yet gaps persisted. Despite near-complete IReV coverage, no automatic anomaly detection flagged transactional irregularities, leaving human agents to reconcile reports with a mixture of rumour and evidence.

High-profile candidate complaints and national commentary elevated the issue beyond local rumour, forcing civil-society organisations like SERAP to publicly demand referrals for investigation and prosecution. The heightened visibility, however, revealed systemic weaknesses: enforcement rarely extended beyond foot soldiers to the financiers orchestrating these transactions.

Source: Twitter

The loopholes that fuel the bazaar

Several interlocking gaps enable this transactional ecosystem. Evidence collection remains weak at polling units. Observers and agents often lack tools to capture admissible time-stamped, geo-located documentation, leaving social media as the primary, yet unreliable, evidence source. Cash distribution networks rely on intermediaries, who can be scapegoated or evade arrest, further insulating sponsors from prosecution.

Even when arrests occur, delays or failures in prosecution reinforce a perception of impunity, signalling to parties that the market for votes carries limited risk. Voter vulnerability shaped by poverty, unemployment, and exclusion ensures a persistent demand. Short-term economic pressures incentivise voters to monetise their ballots, sustaining the cycle despite laws, penalties, or security deployment.

Toward structural repair

Addressing vote-buying requires interventions that extend beyond arrests and rhetoric. At the operational level, INEC and enforcement agencies can standardise evidentiary kits for polling units, equipping observers with time-stamped cameras and secure upload portals. Coordinated standard operating procedures between INEC, EFCC, and ICPC would allow simultaneous monitoring and enforcement without contradictory public messaging. Civil-society organisations should have a formal referral pathway for credible citizen reports, tracked publicly to maintain transparency and trust.

Expanding pre-election social protection schemes like conditional cash transfers, food support, and emergency household top-ups reduces the immediate financial incentive to accept inducements. Campaign finance transparency, enforced through mandatory bank-channelled contributions and audit mechanisms, limits the liquidity available for ad hoc electoral markets.

Strengthening internal party democracy can reduce the centralisation of patronage rent pools, decreasing the reliance on cash inducements to secure loyalty. Investments in local economic resilience (youth employment, microcredit, and MSME development) create sustainable alternatives to transactional survival.

Reconciling security, procedure, and civic dignity

Vote-buying in Anambra exposed more than electoral infractions; it reflected survival pressures, opaque campaign finance, fragmented institutions, and civic alienation. Over 50,000 officers, IReV uploads, and rapid result collation could not secure trust or legitimacy. Piecemeal arrests amid institutional denial deepen cynicism. Meaningful reform requires acknowledging voter precarity, investing in evidence infrastructure, and reducing the profitability of transactional politics.

By addressing these structural and ethical gaps, Nigeria can move toward elections that are both technically secure and morally credible. Only by protecting citizens from desperation and the polity from impunity can the ballot become a true foundation of participatory democracy.

Lekan Olayiwola is a public-facing peace & conflict researcher/policy analyst focused on leadership, ethics, governance, and political legitimacy in fragile states.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Legit.ng.

Proofreading by James Ojo, copy editor at Legit.ng.

Source: Legit.ng