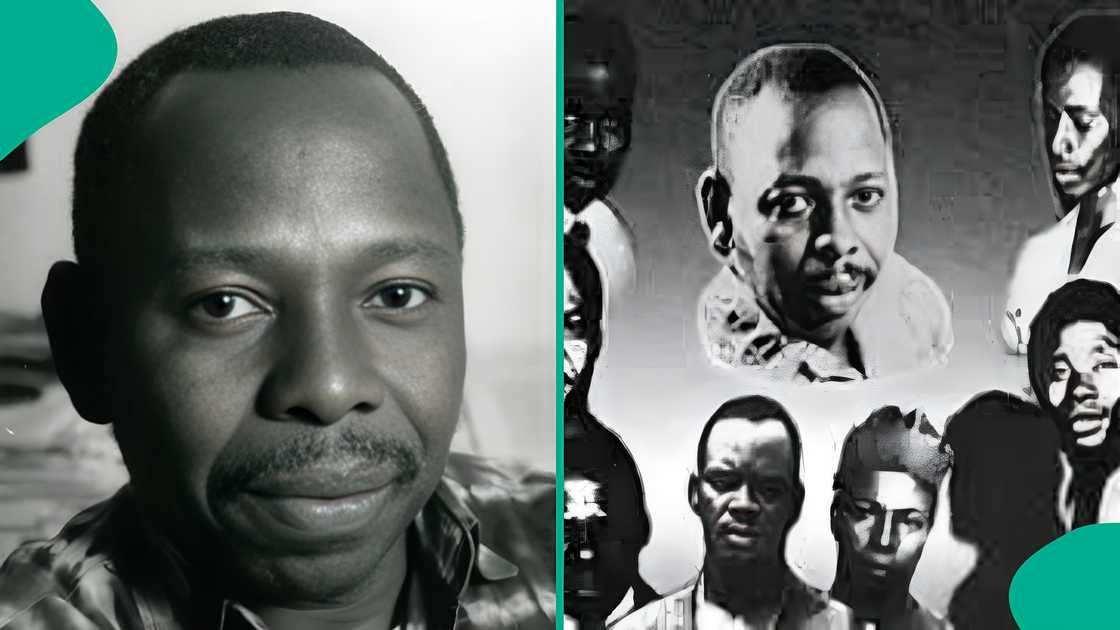

Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni Nine: Is the Posthumous Pardon by President Bola Tinubu Constitutional?

Editor’s note: In this piece, David Bassey Antia examines the constitutional validity of posthumous pardons in Nigeria, using President Tinubu’s recent pardon of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni Nine to question the legal reach of executive mercy beyond death.

On June 12th, 2025, during the commemoration of Nigeria’s Democracy Day, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu undertook a symbolic yet historically significant act of posthumously pardoning Ken Saro-Wiwa and the other eight Ogoni activists who were executed by the military regime of General Sani Abacha in 1995.

Source: Twitter

In so doing, the President reached deep into the dust-laden archives of our national conscience, confronting one of the darkest episodes in Nigeria’s human rights history. This act, though symbolic, deserves commendation, not only for its historical sensitivity but also for its moral courage. It reflects a rare willingness by a sitting Nigerian President to engage the past not as a dreamscape unworthy of attention, but as a living memory with enduring implications. What the President did is a recognition that the past is not a deserted museum of obsolete injustices, but a living reality that demands attentive care, moral reckoning, and, if possible, redemptive gestures.

The execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and his compatriots remains a chilling emblem of the state’s brutal suppression of dissent. In fact, it may be said that among Nigeria’s most enduring injustices, the tragic episode of Ken Saro-Wiwa and the nine Ogonis enjoys sober distinction. These were men whose only crime was to demand environmental justice and the right to development for their people. They were hanged by the state after what has consistently been described as a deeply flawed trial process. Ogoni land, rich in oil, was visited not with compensation or development, but with the ferocity of extraction, stripped and spoiled like the reckless burglary of a home. There was no proximate intervention of conscience. Theirs was a fate met at the intersection of activism and tyranny.

While the President's gesture is laudable, it provokes a profound constitutional inquiry, which is whether the President can, by virtue of Section 175 of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), validly grant a pardon to individuals who are deceased? In other words, does the Constitution contemplate the extension of the prerogative of mercy to those who, in the eyes of the law, no longer possess legal personality?

Can the arm of executive grace reach beyond the grave?

The constitutional basis for the grant of pardon is found in Sections 175 and 212 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended). Section 175(1) provides that “The President may—(a) grant any person concerned with or convicted of any offence created by an Act of the National Assembly a pardon, either free or subject to lawful conditions.” It is therefore settled that the prerogative of mercy is exclusively an executive function, exercisable only by the President at the federal level and the Governor at the state level.

Read also

Peter Obi drops bombshell, mentions how Tinubu “In 2 years, borrowed more money than 3 presidents combined”

This power is far-reaching but not unfettered. As the United States Supreme Court noted in Biddle v. Perovich (1927), a pardon is not merely a private act of grace but an integral part of the constitutional framework. In Nigeria, this principle is affirmed in Falae v. Obasanjo (1999) 4 NWLR (Pt. 599) 476, where the Court of Appeal defined a pardon as “an act of grace by the appropriate authority which mitigates or obliterates the punishment the law demands for the offence and restores the rights and privileges forfeited on account of the offence.”

The effect of a pardon, properly granted, is to render the individual a novus homo—a new man. However, a pardon is not a declaration of innocence. It is not synonymous with acquittal. Rather, it suspends or erases the punitive consequences of conviction without necessarily nullifying the historical fact of guilt.

But can a person be pardoned before conviction or after death? This question has provoked divergent judicial opinions. The prevailing view remains that a pardon presupposes a conviction. In C.O.P. v. Ali (2003) FWLR (Pt. 157) 1164 at 1180 (CA), the Court of Appeal emphasized that guilt must exist before a pardon can be granted, consistent with the constitutional presumption of innocence under Section 36. Similarly, in Obidike v. State (2001) 17 NWLR (Pt. 743) 601 and Solola v. State (2005) All NLR 443, the Supreme Court held that a person with a pending appeal against a death sentence cannot be validly pardoned under Sections 175 or 212 until the appeal is concluded. Yet, the Court of Appeal in FRN v. Alkali & Anor (2018) LPELR-45237(CA) ventured a different path, suggesting that the phrase “any person concerned with” in Section 212(1)(a) could be interpreted to include individuals still on trial. This proposition remains unsettled and arguably inconsistent with settled law.

Turning now to the specific issue of posthumous pardon, the question becomes whether a deceased individual retains legal personality for the purpose of benefiting from a presidential pardon. It is axiomatic in law that death extinguishes legal personality. In Margaret Nzom & Anor v. Jinadu (1987) LPELR-SC 113/1985, the Supreme Court stated without equivocation: “dead men are no longer persons in the eyes of the law.” The court further observed that “the personality of a human being is extinguished by his death.” This principle of common law—actio personalis moritur cúm persona—has been affirmed in numerous decisions, including Abamo & Ors v. Bamigbose & Ors (2016) LPELR-41947 (CA), and even as far back as Baker v. Bolton (1808) 1 Camp 493

Source: Twitter

In Udeogaranya v. Adeyi (2010) LPELR-CA/I/M.115/2003, the court reiterated that the word “person” under Nigerian law refers either to a natural person—meaning a living human being—or to an artificial legal person, such as a corporation. In Fawehinmi v. NBA (No. 2) (1989) 2 NWLR (Pt. 105) 558 at 627, the court further clarified that a natural person is “a human person who has life and blood in him or her,” whether a citizen or non-citizen. Thus, can the late Ken Saro-Wiwa and the other compatriots of Ogoni land fall within the constitutional meaning of “any person” as used in Section 175(1)? The answer must be approached with sober legal logic.

Judicial authorities suggest that the answer is no. Apart from the reasons articulated in the foregoing, one way to consider judicial authorities on what happens to a court case when one of the parties is deceased. In Re: Otuedon (1995) 4 NWLR (Pt. 392) 655 at 667, it was held that a judgment delivered in favour of or against a deceased person who was not properly substituted before the court is a nullity. In Busari & Ors v. Oseni (2018) LPELR-46635(CA), the Court of Appeal affirmed that such a judgment is destitute of legal force. If a court cannot adjudicate for or against the dead, can the President validly confer a pardon on a dead person?

The inescapable conclusion is that, under the existing constitutional framework, a posthumous pardon is legally ineffective and arguably unconstitutional. The deceased no longer possesses the legal identity necessary to receive an executive pardon. The constitutional phrase “any person concerned with or convicted of” presupposes the existence of legal personality.

That said, posthumous pardons are not entirely without precedent or utility. They often serve symbolic purposes, which include correcting historical wrongs, acknowledging state failures, and healing national wounds. President Tinubu’s gesture mirrors President Donald Trump’s 2018 posthumous pardon of Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight boxing champion, whose conviction in 1913 was widely condemned as racially motivated.

Given the moral and symbolic utility of such gestures, it is respectfully submitted that the National Assembly should consider enacting legislation to formally provide for posthumous pardons. Such a statute could empower the President to issue posthumous pardons under well-defined conditions that uphold the values of justice and national reconciliation, while shielding the power from political abuse. Alternatively, a constitutional amendment may be pursued to expressly authorise this power under the framework of Sections 175 and 212.

Until then, however noble the intention, the posthumous pardon granted remains without a solid constitutional foundation.

Read also

June 12: After 32 years, activists, coalition send crucial message to Tinubu, “Remember the sacrifice”

David Bassey Antia is a member of the Faculty of Law at Topfaith University, Mkpatak. He currently serves as President of the Council of Topfaith University Students (COTUS).

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Legit.ng.

Proofreading by James Ojo, copy editor at Legit.ng.

Source: Legit.ng