2027 Polls: Why Nigeria Cannot Afford Another Election Under a Broken Law

Editor’s note: In this piece, governance expert Kalu Okoronkwo looks at how gaps in Nigeria’s Electoral Act 2022 could affect the 2027 elections. The communications strategist explains why fixing these rules now is crucial for fair and trusted polls.

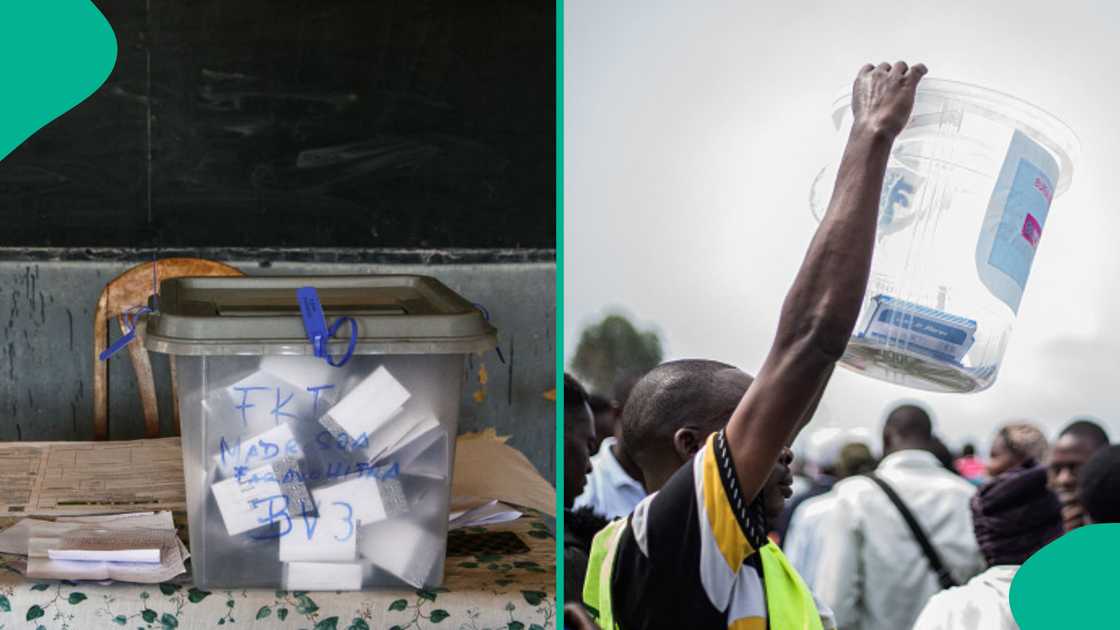

As Nigeria prepares for the 2027 general election, one policy reality stands above all others: the urgent amendment of the Electoral Act 2022. This is no longer a discretionary reform agenda or a matter of political convenience; it is a foundational requirement for electoral integrity. Without timely legislative correction of its loopholes and enforcement failures, the prospect of a credible 2027 election is structurally undermined.

Source: Twitter

The Electoral Act 2022 was widely celebrated upon enactment as a landmark reform. However, its first real test during the 2023 general election exposed deep structural weaknesses. Gaps in enforcement, ambiguities in critical provisions, and insufficient legal clarity on the use of technology combined to produce an election that was widely disputed and legally difficult to challenge.

Petitioners encountered near-insurmountable procedural hurdles, while alleged infractions often went unpunished, not because wrongdoing could not be established, but because the law itself constrained accountability.

Why is the Electoral Act 2022 insufficient for 2027?

Historically, Nigeria’s electoral framework has evolved through periodic reforms. Since the return to democracy, the National Assembly, often in collaboration with INEC, has amended electoral laws before and after general elections to address observed shortcomings. Reform, in this sense, has been both iterative and responsive.

Yet experience shows that as electoral safeguards improve, efforts by political actors to circumvent them intensify. The 2023 elections did more than expose operational lapses; they revealed a more dangerous flaw, an Electoral Act riddled with loopholes that made manipulation easier and accountability elusive. The consequences were visible: widespread irregularities on election day and a post-election legal process so constricted that petitioners struggled to meaningfully advance their cases in court.

When the rules governing elections make redress impracticable, democracy itself is quietly subverted. The central lesson of 2023 is clear: continuing to rely on the Electoral Act 2022 for the 2027 elections is not merely risky, it is reckless.

The Act was enacted on the assumption that a modern legal framework would address chronic problems of manipulation, impunity, operational inefficiency, and institutional weakness. While it remains the most progressive electoral legislation in Nigeria’s recent history and produced some positive outcomes, its first application exposed significant legal ambiguities.

Loopholes in election result transmission and procedures

These ambiguities became the basis for extensive post-election litigation. Among them was uncertainty over the hierarchy and timing for comparing physical results with electronically transmitted results. Key terms such as “transmitted directly” and “electronically transmitted,” used in Sections 60 and 64 on collation of results, were left undefined, creating confusion over whether they referred to electronic transmission.

Although INEC is empowered to review declarations or returns made under duress or contrary to law, the Act fails to prescribe clear procedures for exercising this authority. Section 65(1) does not specify who may file a report alleging unlawful declarations, nor does it outline the process for such filings. This vacuum has fueled controversy and legal uncertainty.

Over-voting remains another persistent challenge. Under the Electoral Act 2022, over-voting occurs when votes cast exceed the number of accredited voters. Current jurisprudence imposes an onerous evidentiary burden on petitioners, requiring them to tender the voter register, BVAS machines, and polling-unit-level result sheets (Form EC8A). Failure to meet these requirements is fatal to a petition.

Read also

Senate President Akpabio discloses when Nigeria’s Electoral Act will be ready for 2027 polls

This burden is particularly unfair given that INEC is the custodian of these materials and has, in some instances, including the presidential election petitions, been reluctant to produce them. The problem is compounded by the sui generis nature of election petitions, which operate under rigid timelines that cannot be extended.

Another major defect of the Act is the absence of statutory backing for INEC’s procedural and technological innovations. Nigeria’s apex court has held that INEC is not legally mandated to electronically transmit results. The IReV portal, the Supreme Court ruled, is not part of the collation system but merely a viewing platform. As a result, electronic transmission was effectively disregarded because it is not explicitly provided for in the Electoral Act 2022 and exists only in INEC’s Regulations and Guidelines.

How legal gaps, tech issues threaten electoral transparency

These deficiencies underscore why the Nigerian Senate’s role is pivotal. Constitutionally empowered to refine and strengthen electoral laws, the Senate carries a responsibility that transcends partisan interests. Legislative delay in this context is not neutral. Every moment of foot-dragging deepens uncertainty, suspicion, and distrust. Failure to amend a defective law does not merely postpone reform; it imperils the next election.

Source: Getty Images

INEC’s role is equally critical. While it does not legislate, its operational experience positions it as an indispensable catalyst for reform. No institution understands the Act’s deficiencies better than the one tasked with implementing it. INEC’s responsibility, therefore, extends beyond administration to advocacy, providing evidence-based recommendations, flagging legal ambiguities, and publicly pressing for timely amendments that enable transparent and credible elections.

Globally, respected electoral commissions play this role without hesitation. India’s Election Commission routinely pushes for legislative updates. South Africa’s IEC actively engages Parliament to safeguard electoral integrity. Silence in the face of a flawed legal framework is not neutrality; it is institutional failure.

Across democracies, elections are governed by what political scientists call the “rules of the game.” When those rules are weak or ambiguous, they invite abuse. As The Economist has repeatedly warned, flawed electoral frameworks do not merely produce disputed outcomes; they corrode public trust and normalize cynicism. In the United States, post-2000 reforms followed the Florida recount because lawmakers recognized that no democracy can survive repeated elections under known defective laws. Kenya’s sweeping reforms after the 2007 crisis were driven by the same realization.

The loopholes exposed in the 2023 elections were not abstract technicalities. They shaped real outcomes, allowing discretion where clarity was required, silence where sanctions were necessary, and procedural barriers that shielded malpractice from judicial scrutiny. The result was an election widely perceived as compromised and a legal aftermath that left many Nigerians convinced that justice was structurally out of reach.

Ordinarily, such a moment would prompt urgent legislative action. Yet nearly two years later, the Senate’s posture reflects inertia rather than urgency. Despite broad consensus among civil society, legal experts, and election observers that substantial amendments are needed before 2027, the process has stalled. A recent investigative report by the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ) does more than sound an alarm; it indicts the Senate’s lack of seriousness at a critical national juncture.

How the Senate can ensure electoral credibility

The credibility of the next general election now hinges on the speed and seriousness with which the Senate acts. Each month of delay deepens suspicion that inaction may be strategic rather than accidental. When lawmakers refuse to fix known defects, they effectively privilege outcomes over process and advantage over fairness.

No democracy should conduct two consecutive elections under a legal framework already shown to facilitate manipulation. Doing so is not reform; it is abdication. It signals that electoral credibility is negotiable and public confidence expendable.

The stakes are immense. A credible 2027 election is not merely about who wins or loses power; it is about restoring confidence that votes count, disputes can be fairly resolved, and democracy remains the accepted pathway for political competition. As the Financial Times has observed, once citizens lose faith in elections, they begin to seek alternatives, and those alternatives are rarely democratic.

Urgent, transparent, and comprehensive amendment of the Electoral Act 2022 is therefore the clearest signal that Nigeria has learned from 2023. It is the legal firewall against repeating past failures. Without it, every promise of a credible 2027 election rings hollow.

The Senate still has a narrow window to change course. Passing a robustly amended Electoral Act, one that closes loopholes, strengthens transparency, and restores faith in judicial remedies, is not a concession to opposition parties or civil society; it is a duty owed to the electorate.

Anything less is not neutrality; it is complicity. History, in Nigeria and elsewhere, is unforgiving to institutions that had the power to defend democracy and chose instead to look away.

The Senate must act with urgency, not excuses. INEC must lead with clarity, not caution. Civil society and the media must sustain pressure, not fatigue. Nigeria still has time to get it right, but time, once lost, has a habit of returning as a crisis.

Kalu Okoronkwo is a communications strategist, a leadership and good governance advocate dedicated to impactful societal development, and can be reached via kalu.okoronkwo@gmail.com.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Legit.ng.

Source: Legit.ng