Hope Dangles for Women, Children Displaced by Benue, Kogi Floods

- The flooding in Nigeria has continued to affect many households and businesses across the country

- Those hit hard by the effect of the flood including women - nursing mothers - and their children whom some basic needs of life have become a luxury to them

- In Benue and Kogi states, these women narrate their ordeal in Internally Displaced Person Camp and the dejection they face living as 'refugees' in their own land

PAY ATTENTION: See you at Legit.ng Media Literacy Webinar! Register for free now!

Amina Usman was about 35 weeks pregnant when like other residents of Akpaku village, Koton-Karfe Local Government Area of Kogi State began noticing the rising water level at a nearby stream that connects to the Koton-Karfe river. Rather than recede, the water level continued to increase as the days went by.

A devout Muslim, Amina and her family prayed that their two-bedroom bungalow would enjoy some supernatural protection against the flood. On the advice of neighbours, her husband decided to hide their clothes, foodstuff, and other valuables in the ceiling, hoping against all odds that the water would not exceed the window level just like in 2020.

Unfortunately, what Amina and her family did not know was that the flood would threaten the lives of the entire community and hundreds of others in Kogi, Benue, Bayelsa, and 28 other states in Nigeria, including Abuja, the nation’s capital territory.

On the night of Thursday, 22 September 2022, the same stream, which served as a means of livelihood and water source for the predominantly fishing community in Kogi State, became their biggest nightmare.

Source: UGC

PAY ATTENTION: Share your outstanding story with our editors! Please reach us through info@corp.legit.ng!

“The flood water came from that river without warning. It didn’t ask who was pregnant, young, or old. It came for our lives and all that we had. Our entire community is now underwater,” she said in Ebira, a language spoken by the Ebira tribe in Nigeria’s North-central states of Kogi, Nasarawa, Niger, Kaduna, and the Federal Capital Territory.

In search of safety, Amina, her family and seventy-eight other households found shelter at Urakpa Primary School, a structure located on the hills along the Abuja-Lokoja expressway, in Koton-Karfe, in the early hours of Friday, September 23.

Abandoned in camp

Settling down at the camp with over a thousand people was an impossible task. An average of 15 households of about six family members each lived in the eleven classrooms. Although this number would reduce to about six hundred three weeks later, it still did not feel like home.

A nearby stream across the busy expressway served as the only source of water for the camp. The poor water supply impacted the sanitary condition of the camp, and soon, as it was only a matter of time, the elliptic water supply led to an outbreak of disease at the camp.

Source: UGC

Officials of the State Emergency Management Authority (SEMA) visited the camp with supplies only once. Mohammed Usman, the camp coordinator, said most help has come from individuals and Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs).

“Our children and women here are battling malaria because they sleep without treated mosquito nets. Some have been diagnosed with cholera, but the government has abandoned this camp. SEMA only came with very few food items, a few mats, and blankets. We need help,” Mr Usman said.

Six babies born in six weeks

Barely four weeks in the camp, Amina had a safe delivery at a hospital in Koton-Karfe town, approximately five kilometres from the camp. And within six weeks, the camp recorded six births.

Source: UGC

The birth of children, which usually heralds the coming of good and the promise that things would get better, wasn’t the same for these families. Most of the women were unable to pay their hospital bills and get the required drug.

Commenting on this, Martha Adeniran-Joseph, a private medical practitioner, said it could endanger their lives and that of the babies.

“These essential drug given to mothers after the birth of a baby help to, among other things, repair tissues and prevent postpartum haemorrhage that may lead to the death of the mother. It’s dangerous not to buy or take them,” she said.

According to her, rest for the mother and exclusive breastfeeding are essential during the postnatal period, adding that a balanced diet is important to achieve the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding. But at the camp nursing women only eat whatever is available.

Source: UGC

Statistics from the World Health Organisation indicate that Nigeria has a maternal mortality rate of 512 per 100,000 births accounting for over 34 per cent of global maternal deaths– the worst in the world.

Women count losses in Lokoja

When the flood overflowed the banks of the Meme River in the Adankolo area of Lokoja, Florence Amuya thought it would not go beyond the street behind her apartment.

“We kept praying that it would not get to our house,” she said.

But the water kept inching closer with an unfathomable vengeance. Three days later, her family could no longer bear the stench as the water had begun flowing into her kitchen and living room.

In another four days, her house and over a hundred others have been completely submerged in the water.

Source: UGC

After a month of nomadic existence due to the living conditions at the internally displaced persons camp, Florence decided to return home with her family.

“I have three children. I had to keep them with church members and friends in areas that were not affected by the flood. Personally, things have been so rough for me. All my property were destroyed in spite of the situation in the country. How will I replace them? No money, food, or anything” she said.

While things are not ideal at home, for Florence, having a space she can call hers and share with her children is important. And like every good parent, she is prepared to fight so her children can have a shot at normalcy.

She said home remains a place full of hope, and a proverbial cornerstone, one, she can stand on and build back better.

Source: UGC

Like other women at the camp in St Luke Primary School, Adankolo, Aisha Abubakar had taken a loan to enable her to cultivate millet, maize, and groundnuts at her farm.

With barely two months to harvest, her farm and house were overtaken by the flood water in September.

She currently stays at the makeshift camp for displaced residents where families must scramble for food, water and other supplies.

“I took a loan so I can farm. Right now, I don’t know how I’ll pay back as the farm has been totally swallowed up by water. I have seven children and they cannot go to school.

"No money, nothing. Even the clothes on my body, some people brought them for us. We are all empty. Like newborn babies- naked. We got food supplies five days ago,” she said.

But for every Ms Abubakar who told her story, there are countless untold stories of pain and despair. At the camp, women who were strangers in many ways had been bound together by shared pain and destitution.

Source: UGC

Alleged food diversion

Unlike Lokoja, residents displaced by the floods in Makurdi, the Benue State capital, had no identified camp. So, when flood water swept its way through to Hadiza Abdullahi’s house in the Wadata area of Makurdi, she was left with no choice but to leave with her four children in the thick of the night.

They spent three weeks with relatives in High Level, Modern Market Road and SRS area of North Bank, all in Markurdi. The Benue State Government, according to Hadiza, provided them with food items after weeks of taking their data and promising to help.

In the end, most of the displaced residents of the communities at the foot of River Benue in Abattoir/Wurukum area of Makurdi received a few cups of rice, sugar, and packets of noodles –barely enough for a family of four.

“The problem is that those who are severely affected by the flood do not get the relief materials. It is those who didn’t suffer any loss that benefits from this the most,” she said.

Hadiza’s expressed displeasure over the alleged corrupt-ridden distribution process in the Makurdi camp echoes the voices and sentiments of displaced residents in Adankolo, Gadumo and Ganaja areas of Lokoja in Kogi State.

Source: UGC

However, Aliyu Adoga, a SEMA official and the camp manager at Adankolo, dismissed allegations of food diversion at the camp. According to him, food and other supplies from the government and NGOs are distributed equally among over 400 inhabitants through representatives of the six classes.

Re-occurring Benue, Kogi floods

For many residents of Nigerian riverine and floating communities, especially those littered along the banks of the Benue and Niger rivers, the annual mid-year torrential rainfalls are symbolic of a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, heavy rains mean a booming fish season would soon roll in, and on the other hand, the rains are a harbinger of impending loss and heartbreak. As the water rises, the very source of sustenance for most of these families becomes a common source of shared pain and despair. In what many would consider a bad year, the flooding that ensues begins as early as late

July, and by August, houses become inhabitable, families are displaced, and for a few of the children who are in school, the school year ends abruptly. And the following year, the cycle of great toil, a booming fish season, and later accompanying untold pain and hopelessness continues.

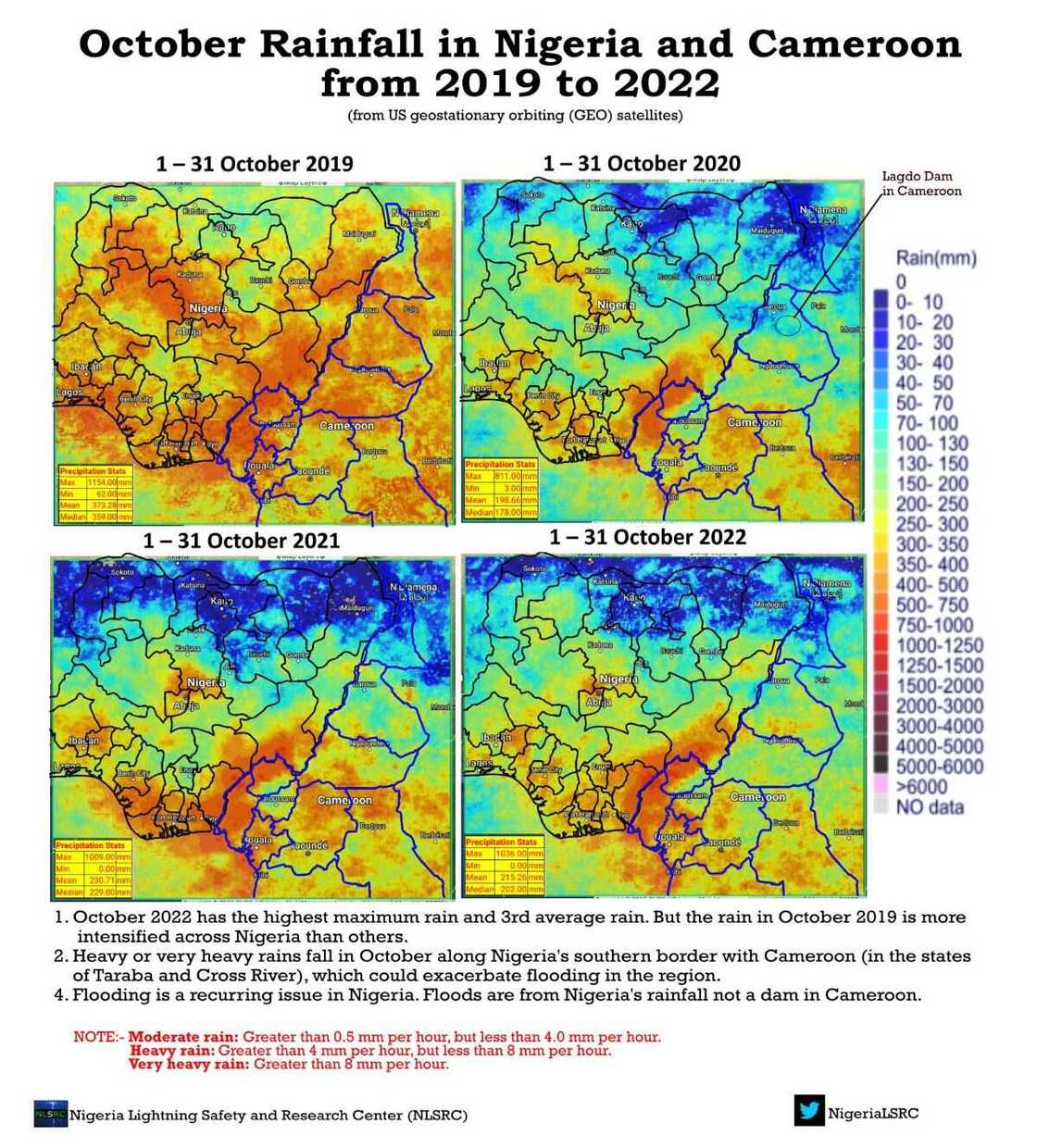

Yet, none of the perennial floodings of the past years prepared these communities for what was to come. So, in 2012, when the Cameroonian authorities released excess water from Lagdo Dam located in the country’s northern province, coupled with increased rainfall at the time, the monstrous water found its way into Rivers Niger in Lokoja and Benue in Makurdi, through their tributaries, the whole country was devastated by the ensuing loss and damage that followed. To date, it remains one of Nigeria’s biggest floods with over two million displaced persons and 363 recorded deaths.

Ten years later, Nigerians who reside close to these two major rivers continue to live in fear every rainy season. Aside from the destruction of properties, the yearly flooding has led to the loss of human lives, and productive hours, an uptick in waterborne infections like Cholera, food insecurity, and astronomical increases in the prices of goods and services across major cities in the country.

In October 2022, the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) said no fewer than 603 persons had died as a result of the floods with over 1.3 million Nigerians displaced. Since June, the country has been thrown into a humanitarian crisis with most communities left to grapple with the challenges of rescuing residents from flooded areas.

However, in September, Government and development partners began charting a way to respond to the crisis by evacuating, settling the displaced persons in camps, and providing relief materials for victims across 31 states.

Source: UGC

Flooding, climate change, and Nigeria’s infrastructure gap

There are claims of the existence of a 1977 agreement between Nigeria and Cameroon to build a dam that would manage the spills from Lagdo. But Nigeria’s minister for water resources, Suleman Adamu, says there is no record of such an agreement.

Like most experts, the minister blamed the situation on increased rainfall – an effect of climate change – and the overflowing of the River Benue.

“I have checked the record of the ministry, there has never been anything like that [agreement],” he said.

“Lagdo Dam only contributes a per cent to Nigeria’s flooding. Eighty per cent of the cause of the flooding is from water that we are blessed with from God,” Adamu told senators while defending the budget of his ministry in October 2022.

Source: UGC

But relying on available evidence, Tobi Oluwatola, an energy expert and executive director of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID), said the flooding in Nigeria is both a climate change issue (unpredictable rainfall patterns) and the lack of infrastructure to mitigate the effects of these changes.

In February 2022, the Nigeria Meteorological Agency (NIMET) predicted that the year’s rainfall would result in flooding that may likely wash away houses, structures, and farmlands in the country.

The meteorological agency further advised state governments to take appropriate steps to prevent the occurrence as more rainfall was expected between late August and early October.

It is trite knowledge that one of the ways the governments of the affected states can mitigate the impact of the flood and other natural disasters on vulnerable communities is through the effective use of ecological funds. However, corruption and gross mismanagement of funds set aside for adaptation projects continue to put the lives of many at risk.

Source: UGC

Is any solution in sight?

For over a decade, governments at all levels have continued to strategise on ways to mitigate the impact of the flood experienced in most states in Nigeria annually. The reality, however, is that these efforts have yielded very few gains.

Evidencing the experience of the Netherlands, Dr Oluwatola said a massive infrastructural resilience creation like Delta Works could solve Nigeria’s flooding problem - forever.

“In 1953, the Netherlands had a very similar flooding situation where the North Sea flooded a huge part of the country, taking about nine per cent of the country’s farmlands and killing about a thousand people. What they did was to institute a big infrastructure project that lasted four years for about $4 billion – the Delta Works,” he said.

“They built about 13 dams, over a thousand meters of dikes and levees. There are precedents globally. What they did was to reduce the probability of that kind of flooding from something that happens a couple of times every hundred years to something that is likely to happen in 4,000 years. It may never happen.”

Source: UGC

Dr Oluwatola noted that building more dams, levees, and dikes as well as the dredging of the River Benue to create more room at the bottom for water to flow would help ameliorate the situation.

According to him, the funds for such infrastructural investments could come through adaptation funding from the global north for projects that would help build the resilience of communities to climate change-related disasters.

He further called for proper town planning to avoid situations where houses are built on waterways.

At the household level, the expert advised regular cleaning of drainages and proper disposal of plastic wastes to prevent blockages, as well as less concrete and more vegetation to help soak up rainwater.

As flood water recedes, Amina and other residents of flood-prone areas who experience this annual displacement can only hope that this would be the last.

This reporting was completed with Goodness Adaoyiche with the support of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development and the Centre for Investigative Journalism’s Open Climate Reporting Initiative.

Source: Legit.ng