In India's Mumbai, the largest slum in Asia is for sale

Source: AFP

Stencilled just above the stairs, the red mark in Mumbai's Dharavi slum is tantamount to an eviction notice for residents like Bipinkumar Padaya.

"I was born here, my father was born here, my grandfather was born here," sighed the 58-year-old government employee.

"But we don't have any choice, we have to vacate."

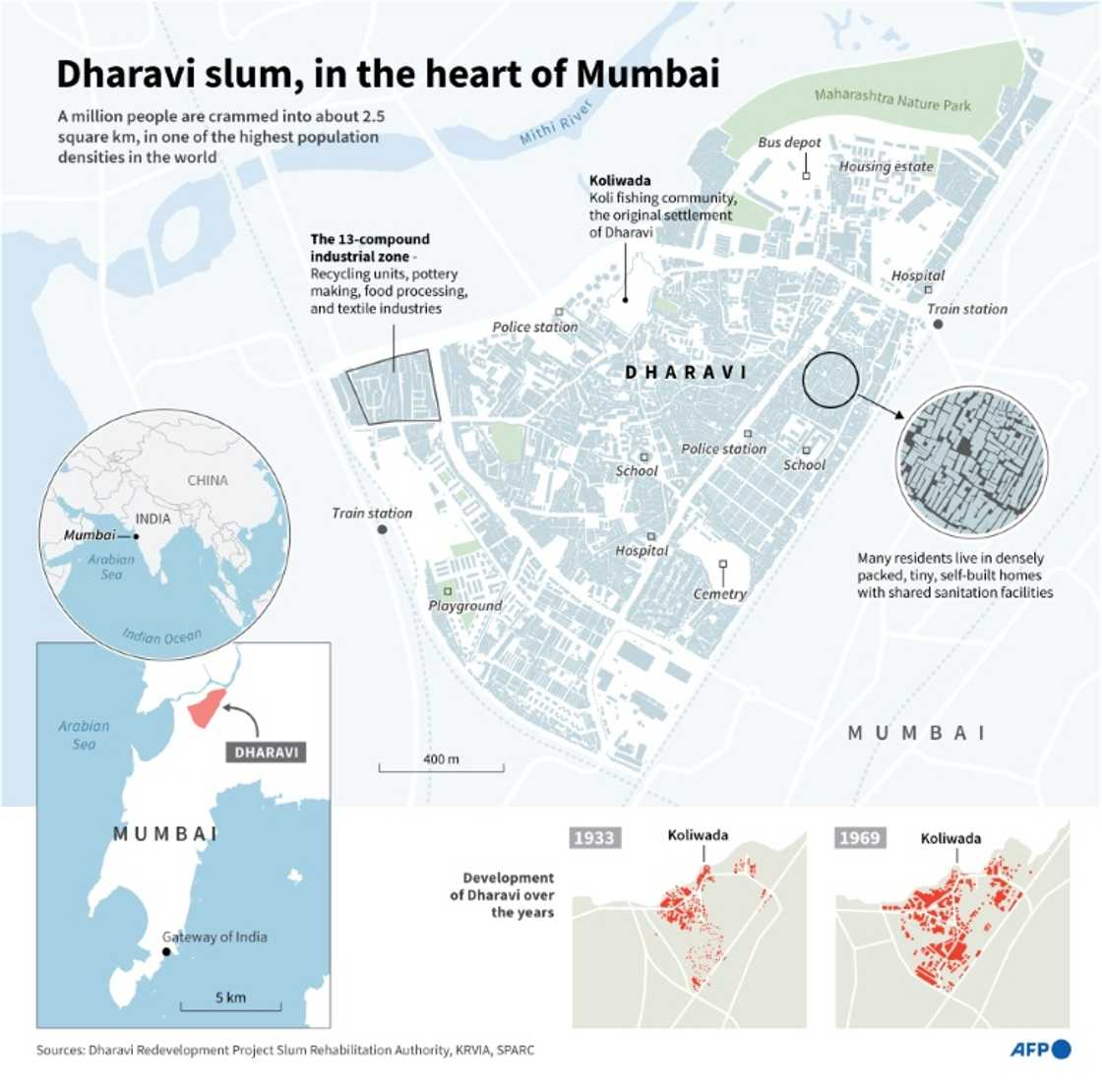

Soon, bulldozers are expected to rumble into Asia's largest slum, in the heart of the Indian megalopolis of Mumbai, flattening its labyrinth of filthy alleyways for a brand-new neighbourhood.

The redevelopment scheme, led by Mumbai authorities and billionaire tycoon Gautam Adani, reflects modern India -- excessive, ambitious, and brutal.

If it goes ahead, many of Dharavi's million residents and workers will be uprooted.

"They told us they will give us houses and then they will develop this area," Padaya said.

"But now they are building their own planned areas and trying to push us out. They are cheating us."

On the fringes of Dharavi, Padaya's one-storey home is crammed into a tangle of alleys so narrow that sunlight barely filters through.

Engine room and underbelly

Source: AFP

Padaya says his ancestors settled in the fishing village of Dharavi in the 19th century, fleeing hunger and floods in Gujarat, 600 kilometres (370 miles) to the north.

Waves of migrants have since swelled the district until it was absorbed into Mumbai, now home to 22 million people.

Today, the sprawl covers 240 hectares and has one of the highest population densities in the world -- nearly 350,000 people per square kilometre.

Homes, workshops and small factories adjoin each other, crammed between two railway lines and a rubbish-choked river.

Over the decades, Dharavi has become both the engine room and the underbelly of India's financial capital.

Potters, tanners and recyclers labour to fire clay, treat hides or dismantle scrap, informal industries that generate an estimated $1 billion annually.

Source: AFP

British director Danny Boyle set his 2008 Oscar-winning film "Slumdog Millionaire" in Dharavi -- a portrayal that residents call a caricature.

For them, the district is unsanitary and poor -- but full of life.

"We live in a slum, but we're very happy here. And we don't want to leave," said Padaya.

'City within a city'

A five-minute walk from Padaya's home, cranes tower above corrugated sheets shielding construction.

The redevelopment of Dharavi is underway -- and in his spacious city-centre office, SVR Srinivas insists the project will be exemplary.

"This is the world's largest urban renewal project," said the chief executive of the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP).

Source: AFP

"We are building a city within a city. It is not just a slum development project."

Brochures show new buildings, paved streets, green spaces, and shopping centres.

"Each single family will get a house," Srinivas promised. "The idea is to resettle hundreds of thousands of people, as far as possible, in situ inside Dharavi itself."

Businesses will also remain, he added -- though under strict conditions.

Families who lived in Dharavi before 2000 will receive free housing; those who arrived between 2000 and 2011 will be able to buy at a "low" rate.

Newer arrivals will have to rent homes elsewhere.

'A house for a house'

But there is another crucial condition: only ground-floor owners qualify.

Half of Dharavi's people live or work in illegally built upper floors.

Manda Sunil Bhave meets all requirements and beams at the prospect of leaving her cramped two-room flat, where there is not even space to unfold a bed.

"My house is small, if any guest comes, it is embarrassing for us," said the 50-year-old, immaculate in a blue sari.

Source: AFP

"We have been told that we will get a house in Dharavi, with a toilet... it has been my dream for many years."

But many of her neighbours will be forced to leave.

Ullesh Gajakosh, leading the "Save Dharavi" campaign, demands "a house for a house, a shop for a shop".

"We want to get out of the slums... But we do not want them to push us out of Dharavi in the name of development. This is our land."

Gajakosh counts on the support of local businesses, among them 78-year-old leatherworker Wahaj Khan.

"We employ 30 to 40 people," he said, glancing around his workshop. "We are ready for development. But if they do not give us space in Dharavi, our business will be finished."

'A new Dharavi'

Abbas Zakaria Galwani, 46, shares the same concern.

He and the 4,000 other potters in Dharavi even refused to take part in the census of their properties.

"If Adani doesn't give us as much space, or moves us somewhere from here, we will lose," Galwani said.

More than local authorities, it is Adani -- the billionaire tycoon behind the conglomerate -- who has become the lightning rod for criticism.

His fortune has soared since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014. So it was little surprise when his group won the Dharavi contract, pledging to invest around $5 billion.

Source: AFP

Adani holds an 80 percent stake in the project, with the state government controlling the rest. He estimates the overall cost at $7–8 billion and hopes to complete it within seven years.

He has publicly vowed his "good intent" and promised to create "a new Dharavi of dignity, safety and inclusiveness".

Sceptics suspect he's after lucrative real estate.

Dharavi sits on prime land next to the Bandra-Kurla business district -- home to luxury hotels, limousine showrooms and high-tech firms.

"This project has nothing to do with the betterment of people's lives," said Shweta Damle, of the Habitat and Livelihood Welfare Association.

"It has only to do with the betterment of the business of a few people."

She believes that "at best" three-quarters of Dharavi residents will be forced to leave.

"An entire ecosystem will disappear," she warned. "It's going to be a disaster."

Source: AFP